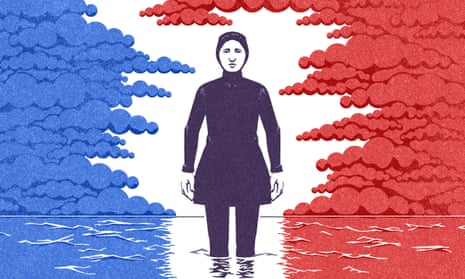

I can’t remember a time in recent history when France has appeared so isolated on an international level because of its own political choices. The criticism that has been levelled at France ever since the burkini scandal broke – especially since the pictures emerged of armed policemen forcing a Muslim woman sitting on a beach to partly undress – has brought to mind other, different, but no less spectacular instances of what some have described as “French-bashing”.

In 2003, when France opposed the Iraq war, anti-French sentiment in America reached such a degree that French fries were renamed “freedom fries” in some restaurants, including Congress cafeterias. In 1995, after France carried out nuclear tests in the Pacific, there was an international boycott of French wines. Now we have seen a demonstration of women denouncing discrimination in front of the French embassy in London, and social media is awash with messages mocking France’s obsession with a piece of clothing.

The burkini ban imposed this month by 30 French municipalities carries so many outright absurdities that it is no surprise there has been a global backlash. How could it be that France’s proclaimed attachment to universal values came to this? How could it be that in Cannes, of all places – on the very beach where in 1953 Brigitte Bardot famously posed in a bikini – women could now be told what they can and can’t wear?

So much has been said about this political, social and moral mess that trying to make sense of it is to risk appearing complacent or in denial about France’s republican or democratic flaws. I’m not. France has dug itself into a hole it needs to climb out of quickly.

But if there is one positive aspect to a situation in which so much confusion, paranoia, racism and hypocrisy have been thrown around, it is that finally a court has clarified what the law says – and what principles need to be upheld. In a keenly awaited ruling, France’s highest administrative court, the Conseil d’Etat, today overturned the burkini ban because, the judges said, “it represents a severe and manifestly illegal threat to fundamental freedoms that are the freedom of coming and going, freedom of conscience and personal freedom”.

The Conseil d’Etat gave no credence whatsoever to claims that the burkini ban, as some of its defenders have claimed, was necessary to uphold laïcité, France’s brand of secularism; nor was it a way of protecting “public order”. In a context where France is still officially in a state of emergency following the recent terror attacks in the country, this is significant.

It took France a long time to find the right balance between respecting the Catholic traditions of many of its people and implementing its 1905 law of separation of church and state. In recent decades, what has been unfolding – and has now taken on an increasingly hysterical dimension – is a new quest for a democratic notion of inclusiveness within French society for Muslims, especially French-born youngsters who feel disenfranchised. None of this has been made easier by the fact that France still has to come to terms with its colonial past, and that terrorism has made toxic passions swirl.

In 1909, the Conseil d’Etat had to rule on an issue not altogether different from today’s burkini question. The city of Sens had at the time outlawed religious processions and even the wearing of cassocks on its streets. Anti-clerical sentiment was so high that the very public appearance of religious clothing was itself deemed disruptive.

But the judges struck down the ban with arguments that strikingly echo today’s ruling. And they included a reminder that the 1905 law was about freedom of conscience just as much as it was about ensuring the “neutrality” of the republic in all things religious (the latter point being, by the way, the reason for the 2004 veil ban in French state schools). Article 1 of the 1905 law guarantees the “free exercise” of any faith, for which “restrictions” can only be made “in the interest of public order”.

French politics today has been upended by the public order question: Nicolas Sarkozy called this week for the banning of all religious clothing in public areas – a message intended to court far-right and anti-Muslim voters ahead of next year’s presidential election.

Claims that the burkini is a threat to “hygiene” or “good manners” have been exposed as completely groundless, but it has been trickier to sweep aside claims that, in France’s tense atmosphere, the burkini might set off scuffles or other violent incidents on French beaches. Many people reading this will immediately jump: applied to beaches in Britain, does that mean a Sikh wearing a turban, or any other person carrying “conspicuous” religious clothing, would represent some sort of risk?

However, it is possible that the mayor of Nice – a city still traumatised by July’s terror attack, and where there have been signs of inter-ethnic tensions – may have had reasonable concerns that racist people might want to attack a woman wearing the burkini. Of course, the first thing to say about this is that upholding public order should be the responsibility of the police – not of women, who must be free to choose their clothes.

But the reason the French prime minister, Manuel Valls, recently shifted from talking about the “enslavement” of women (as a way of explaining his support for the ban) to mentioning “public order” is that this offered a potentially more solid basis for his views – which this week led to a show of divisions within the government. Now the highest court has clearly ruled that neither “public order” nor “emotions linked to terrorist acts” can be invoked to legitimise the ban.

President Hollande has carefully stayed away from the arguments, no doubt waiting for the ruling. But that does little to hide the fact that France’s second socialist president under the Fifth Republic has failed to genuinely reach out to Muslims, especially the young, to reassure them that they will be considered equal citizens, and need not feel overlooked. Again, there is historical precedent: in the 1980s, when the Front National first reared its head, Hollande’s predecessor, François Mitterrand, also missed an opportunity to convey that sense of inclusiveness, despite many slogans heard at the time (such as touche pas à mon pote, for those who remember).

The roots of France’s republican model go back to the battle between church and state, and also to its colonial past. A historian once told me that Britain’s multiculturalism partly points to the way it ran its empire, through “indirect rule”, whereas the French ran theirs directly, in part by settling one million nationals in Algeria.

Today’s ruling is a crucial turning point. It will hopefully restore common decency and the rule of law, and emphasise that the burkini does not in itself threaten public order. If that had been the case, then France’s state of emergency would have meant that, officially, citizens of different backgrounds or faiths could no longer safely sit on a beach together. The ruling isn’t the solution to all the issues that have to be dealt with – that’s some way off. But hopefully it will give a troubled nation some breathing space.