Short term and long, Leave vote is bad news for Ireland's economy

Britain's EU departure will slow Irish economic growth immediately and make us poorer in the future, writes Dan O'Brien

'A UK recession could be shallow and short-lived if businesses quickly regain their poise. But if British consumers were to take fright and pull in their horns too, the slump would be deeper and more protracted'

'Historic' is a much overused adjective, but its use is entirely appropriate to describe the events of recent days.

Britain's vote to exclude itself from Europe's economic and political order is an inflection point in our continent's history. It could well be a turning point. If it is the latter, it will be a turn for the worse. How Brexit happens and how its many consequences are managed will dominate political and economic life for many years to come. We are all likely to be living with the ramifications for the rest of our lives.

But first, let's deal with the short term. Could the shock of Brexit push the Irish economy back into recession?

Three factors will determine whether that happens: how the UK economy performs; what happens to the euro-sterling exchange rate; and how sentiment is affected on this side of the Irish sea.

Britain enters a new uncertain era with fragilities in its economy (more of which anon), but in reasonable short-run shape. Although the economy has been slowing, largely related to Brexit uncertainty, it had decent momentum until Thursday. The shock of Brexit is likely to kill off that momentum.

The greatest vulnerability is corporate investment, which accounts for almost a fifth of UK GDP. If one-in-four British companies postpones investing in plant, machinery and premises for the next six months, that would be enough to push the UK economy into recession.

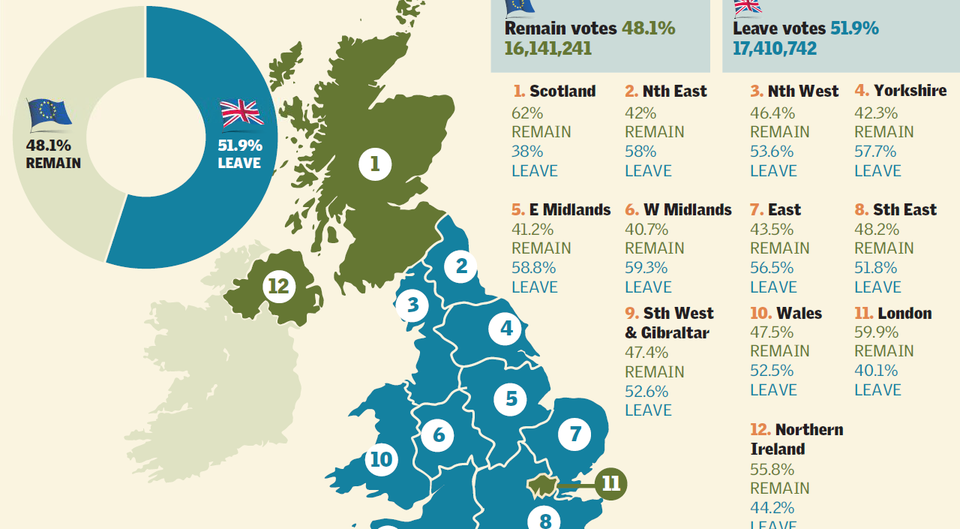

Click to enlarge

As uncertainty is the great killer of investment, and given that there is now so much uncertainty about Britain's future relationship with its neighbours, such a scenario is easy to envisage.

A UK recession could be shallow and short-lived if businesses quickly regain their poise. But if British consumers were to take fright and pull in their horns too, the slump would be deeper and more protracted.

Now, consider the impact on Ireland. Weaker demand in what is still our most important trading partner would push Irish exports to the UK, which were already contracting before Thursday, down further. That would suck momentum out of the economy here.

The second part of what could be a double whammy to Irish exports is the sterling exchange rate vis a vis the euro.

It is well established that sales of many Irish goods and services to Britain are sensitive to changes in the exchange rate. That was abundantly evident before the referendum.

After sterling started weakening last autumn, growth in the value of Irish goods exports slowed. In the first four months of this year, those exports revenues actually contracted, falling by more than 3pc, compared to the same period in 2015.

Predicting movements in currencies is considerably harder than predicting whether companies invest in productive capacity - company bosses are steadier types than skittish financiers. That was to be seen in the immediate reaction to the Brexit vote as the money-men started panic-selling from the early hours of Friday morning.

Over the next 16 hours, until the close of Friday trading, the falls in sterling and London stock prices were among the biggest in history.

Plunging currencies and stock markets do not always lead to bad things happening to the real economy. Sometimes mania remains confined to the financial markets. Black Monday in 1987 was one such example. But as the Lehman Brothers collapse showed in 2008, they can also portend awful economic times.

In this case, the fall in sterling vis-a-vis the euro is based on fundamentals as well as short-term panic. That points to the sterling falling further. That will do more damage to Irish exporters.

The most important fundamental in influencing the price of a country's currency is the gap between what it earns from the world and what it pays out to the world. In Britain, that deficit is now huge. No other big developed economy has such a gap. Nor has it ever been so big in the post-World War Two era.

Large deficits of this size point to an overvalued currency. When currencies are overvalued, they eventually fall. Brexit is just the kind of shock to trigger a correction.

So, to sum up, over the remainder of the year, Irish exports to the UK will be negatively affected by both weaker demand in the British market and by being more expensive, as a result of a weaker sterling. That is the bad news.

The less bad news is that even a very sharp fall in exports to Britain would not be enough in itself to push the Irish economy into recession.

For that to happen, there would have to be a more general loss in confidence here among businesses and/or consumers. Given how unprecedented the current situation is, it is impossible to predict how sentiment here will evolve. My hunch at this point is that Brexit gloom will dampen, but not douse, the recovery.

In sum, the short-term effects on Ireland will be lower growth over the remainder of the year, and the Government is likely to have to revisit its latest fiscal projections which, utterly bizarrely, were published just days before the British vote.

Now, let's turn to the longer term economic impact for Ireland of Britain's departure.

Central in determining the impact will be the economic relationship that is negotiated between the remaining 27 members of the EU and Britain. It needs to be stressed that there will be no bilateral agreements between individual members and the UK, as some commenters have claimed.

The EU market is what economists call a "customs union", meaning that non-members can only do collective deals with the bloc. It is for this reason that Ireland has not done a trade deal with anyone since joining the EU more than four decades ago.

That needs to be repeated because it is, even now, often said that Ireland and Britain will "do a deal" or come "to an arrangement". We won't, unless we leave the EU too.

Another option often mooted is that Britain will join the three countries that are not in the EU, but who are members of the European Economic Area - Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. That is possible, but extremely unlikely.

The most important reason militating against that option is that EEA countries accept EU legislation without having any role in its drafting and enactment.

It is all but impossible to see a UK prime minister who advocated leaving the EU so as "to make our own laws" accepting having laws dictated to his country in this way. That leaves a deal such as the one between the EU and Switzerland, which has more trade barriers than the EEA arrangements; or a deal of the kind that has recently been concluded with Canada, which has even more barriers.

It is also possible that no deal will be reached and that EU-UK trade will be conducted on the basis of World Trade Organisation rules. This would be the worst outcome in terms of additional tariffs and non-tax barriers to trade.

It is important to stress that one of the few things upon which there is universal agreement in the economics profession is that the more barriers there are to commerce, the less commerce there is.

As such, the imposition of tariffs and non-tariff barriers on Irish goods and services being sold into the UK market will make Irish goods less competitive. That will mean less trade over the very long term than there would otherwise have been.

If the outlook for Irish- Britain trade flows is unambiguously bad, the outlook for flows of foreign direct has upsides and downsides.

The solitary upside for Ireland from the Brexit fiasco comes, perhaps paradoxically, as a consequence of new barriers to trade that will go up between Britain and EU.

Companies in the UK, both British and foreign, which service the EU market will have a reason to relocate into the EU so as to avoid those barriers. Services firms, such as those in finance, the law and advertising, will have a particular incentive as new barriers to services are likely to be greater than on most goods.

But tariff-jumping cuts both ways. Companies in Ireland which service the UK market will have an equal incentive to leap over the new barriers and relocate some or all of their operations to Britain.

It is very easy to see an Irish law firm, for instance, move jobs from its Irish operation to its London office to avoid the cost and complication of dealing with the new barriers to selling its services across the Irish Sea.

But given the huge number of British and foreign companies in the UK which depend on access to the EU market, the upside of attracting some of them to Ireland probably outweighs the downside of losing jobs from firms in Ireland.

Rolling out the red carpet to businesses leaving Britain is now an imperative. It is one of the few concrete things Ireland can do to mitigate the many negative effects of Brexit.

This could also have another consequence. As those in Britain who voted to leave read report after report of jobs moving to Ireland (and other EU countries) over the months and years ahead, they may come to think again about their decision.

As the employment effects are felt and some of the promises of the Leave campaign are shown to be nonsense, the campaign already underway for a rerun of the referendum will only gather momentum.

The holding a second referendum on an EU matter would not be unprecedented. In these incredibly uncertain times, nothing can be ruled out.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news